Her name is Asana (AH-sa-nah). When she was just four or five years old she became a student at Heritage Academy in Breman Essiam, Ghana. She rose long before the sun to help her mother with chores, then walked five miles to school, first along the dirt road leading out of her village, then to the partially paved, pot-holed road that washes out during the rainy season, and finally to the main road that buzzes with rickety, beeping, speeding cars. After seven hours of school, she walked another five miles back home to her tiny village in the bush where she did more chores. She went to bed tired and sometimes hungry, but somehow her homework was always done.

Her father died at some point during her young life; it’s not clear to us when. Her mother has a small palm nut oil business. Asana, her mother, and her brother collect the red and black palm nuts from the lush and beautiful palm trees that adorn the landscape. They boil the nuts to make soup, then press the same nuts to make the oil which they sell roadside, as do many other families. They also collect cocoa beans and coconuts to sell, as do many other families. They are grateful for the bounty of the trees around them that provide fruits for food and a very small income, but theirs is a life marked by poverty and struggle.

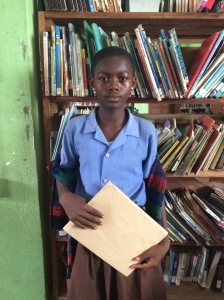

Today Asana is about 12 years old. She’s in 7th grade and a stellar, dedicated student. She is beautiful, but stoic. Her expression carries the wear of hardship. Kwesi Koomson, the founder of Heritage Academy, learned of her long walk to school a couple of years ago and changed the bus route to include a stop close to her home. A welcome relief for Asana.

Today Asana is about 12 years old. She’s in 7th grade and a stellar, dedicated student. She is beautiful, but stoic. Her expression carries the wear of hardship. Kwesi Koomson, the founder of Heritage Academy, learned of her long walk to school a couple of years ago and changed the bus route to include a stop close to her home. A welcome relief for Asana.

One typically hot evening, Kwesi and I had a conversation about our students’ varnished view of the kids at Heritage. It had struck me during last year’s visit that although we were closer than we’d ever been to significant poverty, it remained unseen in many ways. We were surrounded by kids in clean uniforms who were eager, energetic, happy, open, and friendly. We didn’t see their mud-brick and tin-roofed homes with no electricity nor running water. We didn’t see their toil at home. The school provides lunch, so we didn’t appreciate their hunger after the meager meals they got at home (some don’t get any). We didn’t see their worn clothing. I felt uncomfortably aware that we weren’t seeing their “real” lives and I wanted the students to understand them more deeply. Kwesi had long been thinking this very thing about our student trips and decided to arrange a visit to a student’s home. He selected Asana and told us her story. Although I was excited for this closer look, I was worried that our visit might seem exploitative to her family (a bunch of well-heeled foreigners piling into her home to gawk at her living situation), and that Asana might feel uncomfortable. But when he summoned her to ask, she was honored and agreed. She seemed proud, even, as she should be.

As our bus pulled into her village, one made up of about 30 families, the villagers stopped what they were doing to stare. They smiled, but watched us carefully as we disembarked in front of a tiny store that sold sundry items like small packets of laundry detergent and soda. Our students seemed nervous, both for what they were about to see and for being the objects of such intense scrutiny. Many of the villagers don’t encounter foreigners and white people often, if at all.

“Akwaaba” (welcome) her mother said as we nervously shuffled into their tiny compound – a brick house, a wood and tin outbuilding, a storage structure – all surrounded by a wooden fence. Next to the house was large cauldron atop a fire where the palm nuts were boiling in a black liquid emitting an odd, pungent odor. Scattered on the dirt in the courtyard were blackened palm nuts left to dry in the sun. Chickens and ducks (oddly enough) bobbed around our feet. The ubiquitous tiny goats bleated nearby. Asana called for her younger brother who scampered into the courtyard to join us.

We gathered ourselves into a semi-circle with Asana, her mother, and her brother at the fore. I asked the kids if they had any questions for the family. Milo, a young teacher at Heritage Academy, was our translator and guide. Asana’s mother explained how they use the palm nuts. Asana timidly talked some about what her daily life was like; significant was how much work was involved, how little play. Although they seemed happy to have us, it was admittedly somewhat awkward. Our students weren’t sure what they should ask; her family wasn’t sure what they should tell. I could sense that the kids were shocked by the conditions but also impressed by what this family accomplishes with so little. I was too.

We thanked them for showing us their home and I asked if I could take photos of them and their home. They were eager to pose, as are all Ghanaians, who seem to love cameras. As the students left to get back on the bus, I stopped at a table just inside the gate that was covered with a nut I couldn’t identify. The mother approached me and explained – in surprisingly good English – that they were cocoa beans. And then she said in a quiet voice, almost conspiratorially, “I don’t like that she goes to that school, even though she loves it. Her father is passed and I need her to work. I need many hands.” I replied, “It is a hardship for you. You have to choose between earning money and her education?” “Yes, madam, it is hardship. But she smiles.” I looked in her eyes, “You chose her happiness.” She nodded, her lips turning into a small smile, and waved goodbye.

We thanked them for showing us their home and I asked if I could take photos of them and their home. They were eager to pose, as are all Ghanaians, who seem to love cameras. As the students left to get back on the bus, I stopped at a table just inside the gate that was covered with a nut I couldn’t identify. The mother approached me and explained – in surprisingly good English – that they were cocoa beans. And then she said in a quiet voice, almost conspiratorially, “I don’t like that she goes to that school, even though she loves it. Her father is passed and I need her to work. I need many hands.” I replied, “It is a hardship for you. You have to choose between earning money and her education?” “Yes, madam, it is hardship. But she smiles.” I looked in her eyes, “You chose her happiness.” She nodded, her lips turning into a small smile, and waved goodbye.

I’ve thought quite often of Asana’s mother since that day. In Ghana it is common – when only one child in a family can go to school – for the boys to be given the privilege of school over the girls. Girls are often seen as the laborers and keepers of the home, the boys the ones who should be educated. Her mother not only gave up having her eldest child at home to work during the day, but also bucked tradition by giving Asana, not her brother, the opportunity for education. It’s a tremendous sacrifice for her. She needs many hands, but in her world of few choices, she chose her daughter’s education and happiness.

When we think about poverty we often reduce it (as the privileged are wont to do) to the lack of material things, maybe to hunger. We can fleetingly imagine, perhaps, a life without a cell phone, a vast wardrobe, or three meals a day. We tend to forget the intangible luxuries and privileges we enjoy like choice, opportunity, education, freedom, and the pursuit of happiness and dreams. Apart from lacking clean water, ample sources of protein-rich food, electricity, and money, they lack opportunities to choose a different path in life. Those with great ideas, curious minds, and big dreams are left wanting.

And that’s why Heritage Academy is so very important. An education at Heritage provides opportunities that these kids would not otherwise have. They graduate literate, nearly fluent in English, and have distinct advantages over their peers who have no education. They still face monumental struggles of course, for the cycle of poverty is deep and powerful, but they have better footing in their small world. Most of the students at Heritage attend on scholarships provided by the Schoerke Foundation, founded by Kwesi’s wife, Melissa. The many hands (and many donors) of the foundation keep the school in operation, and give kids like Asana a chance.

I came away from this journey, once again, with renewed gratitude for my good fortune and immense thankfulness that my own daughters can pursue their dreams without great sacrifice. None of us will forget that visit to Asana’s home. And I will never forget her mother, whose little smile told me that she was proud both of Asana and her own difficult choice.

Thanks for sharing, Lynette. Such a beautiful family. I’m grateful her mom is making the sacrifice. Its heart wrenching they have to make choices between their children.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Beautiful understated piece of writing. So moving

LikeLike

Thank you, Ne. ❤

LikeLike